Submitted by Thomas Kolbe

Economic indicators suggest a stabilization in Germany’s services sector. Yet the apparent improvement in the corresponding index follows massive staff reductions and efficiency measures undertaken by companies responding to a political structural crisis.

In Berlin, the great tremor has begun. For almost exactly seven months now, the German economy has been pregnant with the federal government’s oversized debt package—and from an economic standpoint, it has delivered nothing so far. No growth in sight. Disappointment is spreading through the government quarter.

Any attempt to explain to politicians that artificial state demand creates no real value but merely beautifies GDP statistics would likely be pearls before swine. And yet Chancellor Friedrich Merz and his cabinet are hoping for positive economic headlines to somehow stumble across the finish line of the 2026 super-election year.

A Flicker of Hope

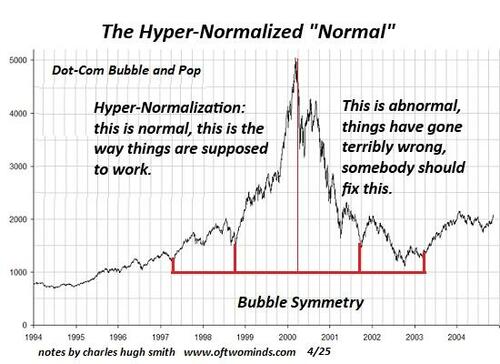

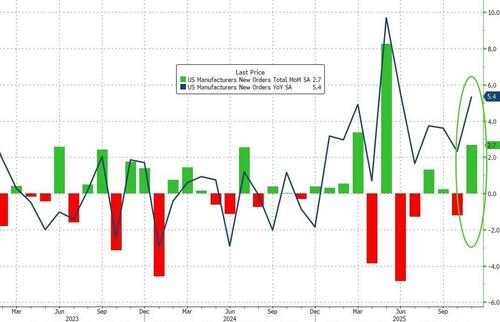

As if an early success story had been ordered at the push of a button, the HCOB Services PMI (Purchasing Managers’ Index) reported an increase in January from 52.7 to 53.3 points—a three-month high.

A figure that fuels false hopes in Berlin. Because what lies beneath the data is almost precisely the opposite of what would now be urgently required: Germany’s services sector is cleaning up its balance sheets, shedding staff on a massive scale in order to realize short-term efficiency gains. What we are witnessing is the forced reaction of the economy to ever-rising energy costs and higher input prices, which—made visible through the inflation index—are passed on to customers and artificially inflate the headline figures. Adjusted for prices, the downturn continues.

Meanwhile, the countless new regulations raining down on the economy from Brussels and Berlin ensure that this diagnosis will not change. A whole bundle of new emissions rules, border adjustment mechanisms, data-usage standards, and countless other ideas from the EU’s industrious bureaucratic think tanks are making life even harder for companies—presumably the much-praised “debureaucratization” that Friedrich Merz keeps fantasizing about.

Let us consider another data point that highlights the depth of Germany’s economic crisis. Current figures from the hospitality sector show that more than 97,000 applicants are now competing for just 19,000 open positions.

Last year, the sector lost roughly four percent of its real business volume, and layoffs are now following the sharp downturn. The hospitality industry crystallizes the collapse of German purchasing power, as households—after years of inflation and a deteriorating labor market—are forced to tighten their belts.

It cannot be emphasized often enough: the long-cultivated narrative of a German “skilled labor shortage,” promoted by politics and the media for years, was from the outset a political vehicle to flank open-border policies. Genuine skill shortages are addressed by companies through the international labor market—by the private sector, not through state-driven mass immigration into Germany’s welfare system. The political left has made the expansion of its voter base a strategic objective, and no reversal in migration policy is in sight.

Here, at the economic front line of the domestic economy, political deception is laid bare. Unemployment will become an economic reality in the coming years, and it will place a heavy burden on social life in Germany.

The State Creates a Buffer

Meanwhile, the inevitable is unfolding in the economy: companies are cutting staff and raising prices wherever possible, making overall economic indicators appear more positive than they truly are—without any real new demand emerging. At the same time, selected firms benefit from state-subsidized projects in areas such as climate policy or military production, further reinforcing the illusion of expansion.

The index figures obscure another crucial aspect of the labor-market debate. Last year, official unemployment in Germany rose by just over 100,000 people. This figure masks the reality that many workers were shifted into short-time work, the number of pensioners increased, and—contrary to the government’s political folklore—the state continued to systematically expand the public sector.

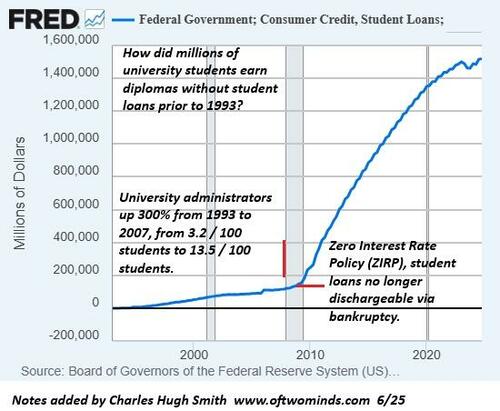

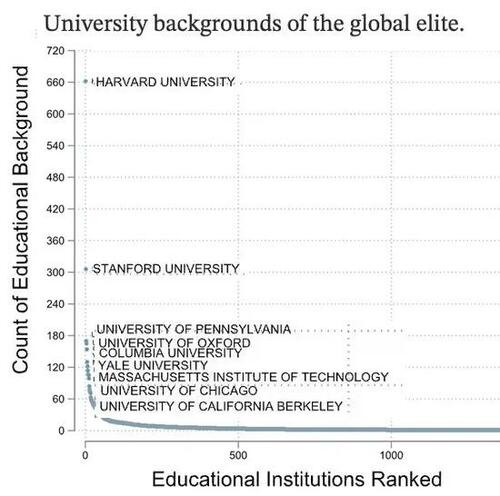

Over the past five years, the number of public employees has grown annually between 1.8 and 2.6 percent. Over the past decade, nearly one million new state employees have been added. Today, five and a half million people work in Germany’s public sector—a bloated machine of capital destruction.

Projecting this continuous expansion forward into 2025, the number of public employees will likely have increased by another 100,000. This is all the more plausible given that distributing the massive new debt package of more than €50 billion per year from the special fund requires a vast regional bureaucracy that far exceeds existing personnel capacities.

Through the costly expansion of its administrative apparatus, the state is masking rising unemployment—a consequence of regulatory policy and the energy crisis that can no longer be concealed—and has driven the German economy into progressive deindustrialization.

The Source of Prosperity

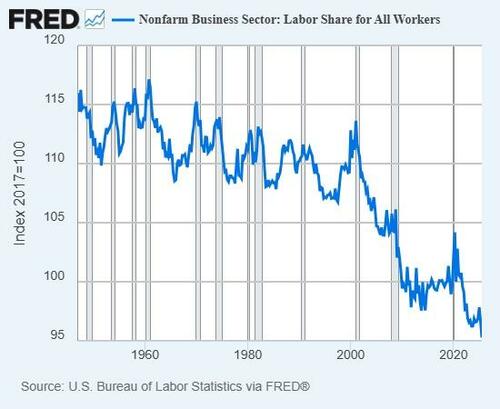

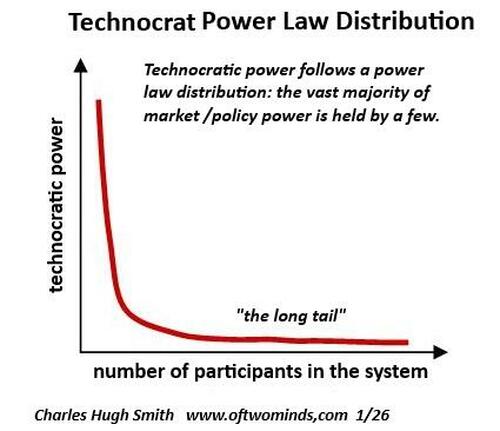

Germany’s economic policy debate lacks substance. It must be emphasized far more clearly that prosperity is exclusively the product of private investment and cannot be conjured up on the drafting tables of central planners in Berlin and Brussels. Only private investment, guided by free markets and consumer demand, expands an economy’s productive capacity.

The “special fund,” the largest state debt program in the history of the Federal Republic, is causing massive crowding-out effects in capital markets. Scarce resources are locked into subsidy schemes, free capital retreats, labor is tied up in unproductive sectors—and the state, in its desperation, fuels the general decline.

These trends are well documented. Figures from the ifo Institute in November show that the investment expectations index fell to −9.2 points. This means a growing number of companies plan to sharply reduce investment this year—especially in industry, where the long-observed trend of capital withdrawal continues. The situation is particularly dramatic in automotive manufacturing, where the index plunged to −36.7 points.

The chemical industry is also fighting for survival. With capacity utilization of only 70 percent, most energy-intensive firms are operating deep in the red. We are facing an economic depression that has manifested itself since 2018 in Germany’s declining industrial output. Overall corporate investment last year was around seven percent below the previous year’s level. Since 2018, German industry has lost more than 15 percent of its production volume.

The country is growing poorer—while poverty migration into the welfare system continues unabated. On a per-capita basis, the effect is even clearer. Germany’s enormous redistribution machine is attempting to conceal the emerging social conflict by intensifying its raid on the middle class through ever more aggressive taxation.

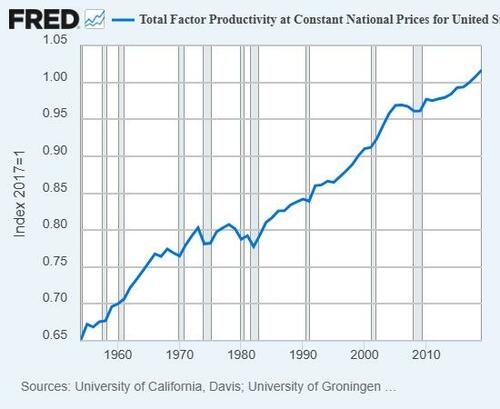

Germany reached its tipping point in 2018. Since then, the economy has stagnated, and overall productivity has declined—a clear indicator that the scaled-up interventionism of the state is crowding out investment capital while expanding a parasitic public sector.

This is a dramatic finding with regard to technological progress, which should have led to massive productivity gains but cannot materialize in Germany amid the flight of companies and capital.

Germany is heading toward growing distributional conflicts. Rising deficits in the social-security system are harbingers of an internal social storm that will unfold along ethnic and cultural lines.

That the state is now rapidly deploying a censorship apparatus to suppress debate about the consequences of these policies should deeply concern everyone. The hastily formulated thesis that “the crisis is the solution” cannot solve individual financial problems, nor can it alleviate fears about personal safety in a country of concrete barriers and knife-free zones.

The collapse of the welfare state shifts economic responsibility and social security back onto individuals. Recovery is possible. It begins when the state is no longer seen as the savior, but as the cause of the present crisis. Until then, the road ahead will be long and rocky.

* * *

About the author: Thomas Kolbe, a German graduate economist, has worked for over 25 years as a journalist and media producer for clients from various industries and business associations. As a publicist, he focuses on economic processes and observes geopolitical events from the perspective of the capital markets. His publications follow a philosophy that focuses on the individual and their right to self-determination.